Garden or paradise?

Few architectures are so utopian, and at the same time so real, as the garden is. Perhaps the etymology of the word can help us to know the reason why. Garden comes from Old French jart, whose meaning was ‘orchard’, which came from Old Low Franconian garda, ‘enclosure’, space that is delimited by a fence. It turns out that, if we trace the origin of the word paradise, we will see it has a Old Persian origin, pairi-daêzã. Pairi means “around”, and daêzã, means, among other things, enclosure. That is to say, paradise is an enclosed space, separated from the world, just like the garden.

Jan Brueghel the Elder, ‘Das Paradies’, c. 1620. Via Wikipedia Commons

The Garden of Eden: paradise beyond

The relationship that is often established between the idea of paradise, and what would be, in the Judeo-Christian tradition, the first inhabited nature, the Garden of Eden, is also a consequence of an etymological journey. It is the result of a translation of the bible, the Greek, also called the Septuagint. This translation of the sacred texts in Hebrew and Aramaic was used by the Jewish communities of the ancient world that lived beyond Judea, and by the early Christian church that spoke Greek. In the Septuagint, the Hebrew word for garden (gan) was mistranslated by the Greek word paradeisos. Eden, on the other hand, would refer to a region where such a garden would be located, “beyond the plains”.

In the Bible, the Garden of Eden is described as a divine space, comfortable, leafy and rich in water. The first man is placed in this paradise by God to protect the Tree of Life. This story coincides with different aspects of Sumerian and Mesopotamian Genesis. In Enûma Elish, a Babylonian poem that narrates the origin of the world, the world was also created in seven days, and began with a garden. In Sumerian mythology, the world starts in the paradisiacal place of Dilmun, today Bahrain.

Finding paradise is an old obsession. The location of this Eden “beyond the plains”, that the Bible describes, has been proposed to be at different points between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

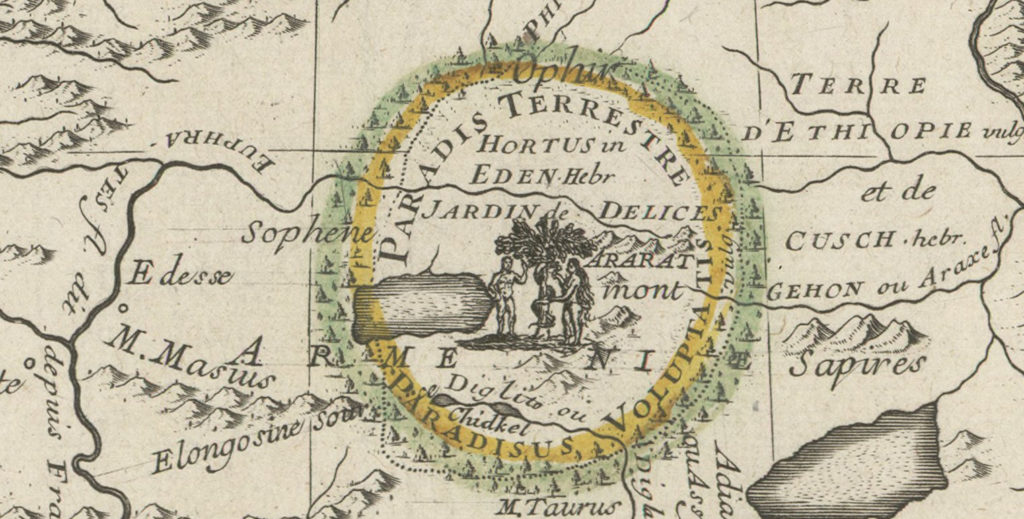

Pierre Moullart-Sanson, ‘Carte du Paradis terrestre selon Moyse’, 1724. This map follows the opinion of Calmet, who at the beginning of the 18th century, locates the terrestrial paradise in Armenia, between the births of the Tigris, Euphrates, Phase and Araxe. Via Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, GE D-13530

Babylon: the hanging garden

Another bad translation is behind the story of another ancient garden. A story that up to recent times seemed to have more of a tale than of an evidence. The wonder of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, in first place, was not supposed to be hanging, but resting on solid arcades built in brick, staggered like a tower or a ziggurat. The Greek word kremastos, which was translated as “to hang”, meant in fact “to overhang”. The description of the Greek Strago said, “it consists of arched vaults, which are situated, one after another, on checkered, cube-like foundations. The checkered foundations, which are hollowed out, are covered so deep with earth that they admit of the largest of trees, having been constructed of baked brick and asphalt — the foundations themselves and the vaults and the arches. The ascent to the uppermost terrace-roofs is made by a stairway; and alongside these stairs there were screws, through which the water was continually conducted up into the garden from the Euphrates by those appointed for this purpose.”

Hypothetical reconstruction of the gardens, elaborated during the 19th century. Via Wikipedia Commons

Lost garden

Traditionally, the Hanging Gardens were imagined to be in Babylon, today called Hillah, next to the Euphrates river. But the precise location always remained unsolved, as archaeological evidence never appeared. This made the old story, saying they had been built in Babylon by King Nebuchadnezzar as a gift to his wife around 600 BC, or by Queen Semiramis around 800 BC, unlikely. No Babylonian text mentioned the Gardens. Perhaps they were purely mythical, the result of an idealized description of a Persian garden. Or maybe, it was the location that was wrong. Greek or Roman literature may have made another translation mistake. The gardens could be actually adjacent to the Tigris river, near to the contemporary city of Mosul, which during the Assyrian empire was called Nineveh. Many cities were called with the epitome of Babylon, and this is what the British researcher Stephanie Dalley affirms. According to the theory of the British historian, the gardens would have been built by King Sennacherib, around 700 BC, in Assyria. The location of the gardens has been determined through satellite images. The myth of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon accompanied the development of the art of gardening throughout its history. Today this territory is ravaged by war, and archaeological remains of ancient cities, buried sometimes less than half a meter deep, are looted, destroyed, in the midst of one of the most dramatic contemporary conflicts.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, engraving of the German edition of 1726 of ‘The Old and New Testaments connected’, Humphrey Prideaux. Via Wikipedia Commons

Islamic Garden

In the Qur’an, the eternal garden, a promise of happiness, is “as wide as the sky and the earth and in its lowlands streams flow”, “trees without spikes give shade”, “fruits hang at ground level”, and it is surrounded by a wall. Numerous gardens appear throughout the text. The garden on earth is an image of the divine paradise, perhaps with resonances of the oasis in the desert. It is a place of rest, or contemplation, analogous to Eden. Shadow, water and the outer enclosure have great importance. Some Islamic gardens survive today, in Albania, Algeria, Iran or Spain, for example, the gardens of the Taj Mahal or the Alhambra.

Chahar Bagh carpet-garden of the seventeenth century. Via Wikipedia Commons

Chahar Bagh: four gardens

One of the classic schemes of the Islamic garden, of Persian origin, is called Chahar Bagh or Charbagh, which means “four gardens”. This type of garden is arranged in a scheme with two perpendicular axes in which four channels carry water to a fountain or central pool. They make reference to the four rivers of paradise, full of milk, honey, wine and water. Perhaps the garden is the architecture that resembles most a habitable representation. In this case, the Chahar Bagh tries to imitate the world.

Chahar bagh of Kabul in the ‘Book of Babur’, the memoirs of Ẓahīr-ud-Dīn Muhammad Bābur, founder of the Mughal Empire. Via Wikipedia Commons

Arcadia

In modern Western thought, on the other hand, the notion of “ideal nature” has not to do so much with a celestial paradise transported to earth, as to a bucolic region lost in time. It is a idilic place of classical tradition, a nostalgic memory of harmony between human and nature, represented through the notion of Arcadia. Arcadia truly exists, and is located in Greece, in the Peloponnese highlands. After the fall of the Roman Empire, it become part of the Byzantine Empire and gained fame as an isolated territory populated by shepherds who led simple lives. It was portrayed by Virgil in the first century AC, and then, idealized during the Renaissance, until it became an imaginary place, in which humans lived in communion with nature, in a happy and simple way.

Nicolas Poussin, ‘Les Bergers d’Arcadie (Et in Arcadia ego)’, 1639. Via Wikipedia Commons

Lost Golden Age, nostalgic utopia

Painting and literature made Arcadia a theme. A Golden Age of abundance and happiness, linked to the idea of the good savage. Lope de Vega imagined her as an enchanted place of eternal spring, tree, fountain and meadow. A landscape even eroticized. “It seems that here the trees were naturally embraced, and the dumb fish moaned by the water currents, and that the sky helped with gentle winds and mild days.”

Thomas Cole’s, ‘The Arcadian or Pastoral State’, 1834. Via Wikipedia Commons

The myth and its colonial translation

At the same time that the Europeans returned to the classic myths, in the Renaissance, they arrived to America. The existing ideas of terrestrial paradise and lost utopias as Arcadia, were recognized in the American landscape. Europeans ignored the histories of American inhabitants. They searched El Dorado, the Juvenile Fountain or the Country of Cinnamon. They devastated, and rearranged in the European way, lots of what they found. A few decades later, the Enlightened tradition and Romanticism would give new impetus to the aspiration of a life in communion with nature. The nostalgia of that lost time that Arcadia stands for is still a utopia that continues today in our society, and in western popular culture.

Bartolomé de las Casas, ‘Very brief account of the destruction of the Indies’, 1552. The Jesuit already in the seventeenth century denounced Western action on American peoples and landscapes. Via Wikipedia Commons

Leave a Reply