«I’m looking for a 2 or 3 bedroom apartment with a terrace or a patio». Confinement during this time of health crisis has led many people, perhaps almost all of us, to think more often about how to improve our current home. Houses and corona virus: prices, quality and the variety of housing offered by the city are all factors that determine our choice. Meanwhile, the home is the most important space in our lives.

Epidemics have historically contributed to define cities. Medical advances in the 19th century identified the connections between health and hygiene. An iconic example of this was John Snow’s map of cholera. This doctor mapped the sick people in London’s Soho in 1854, as well as the water sources. This way he discovered the relationship between contaminated water and disease.

Overcrowded cities, polluted air caused by industry, and lack of sanitation, often coupled with a complex medieval urban form, brought the issue of hygiene into the mainstream of city discussion. This was the case of Barcelona, which today is probably one of the most attractive cities in the world, partly because of its urban diversity and quality. At the beginning of the 19th century, Barcelona was contained within old city walls. Political tension was important, an example of which was the confrontation between local and state power that ended with the bombing of the city in 1842. Meanwhile town development was urgently needed. After a series of failed attempts at expansion, the government of Madrid commissioned civil engineer Ildefons Cerdá to draw up a plan for the expansion of Barcelona.

Cerdá, who began his training as an architect in Barcelona but went on to become an engineer in Madrid, took a classic approach to defining the new city. It was the hypodamic plan, the grid. This pattern provided an open and non-hierarchical basis, where all social classes were equally arranged. It also allowed the development of an area of 1100 hectares.The grid was defined by square blocks of 113 meters on each side. That was a generous and ambitious dimension for the time. Initially the buildings would only be built on two of the sides, taking a variety of positions. Huge courtyards were generated inside, providing light and air to all the houses equally. The inclusion of the bevel at the crossroads would give even more space. The streets, for which he planned a central tram, were 20, 30 and 60 meters wide. Their width was surprisingly anticipatory.

Cerdá’s street. Via Wikipedia Commons.

Cerdá’s concern for mobility, and also for the inclusion of open and landscaped spaces, gave the city an exemplary urban fabric. Cerdá had researched the living conditions of Barcelona’s inhabitants within the city walls on his own. That work was published in 1856 with the name Monograph of the Working Class. Influenced by utopian socialists such as the philosopher Étienne Cabet, he believed in the possibilities of urban infrastructures to improve the quality of life. Consequently, he contributed to introducing sociology into urban planning.

In the Eixample, Catalan architects constructed many of the buildings characteristic of the local modernism and the bourgeois life of the time. Partly for speculative reasons, Cerdá’s plan was progressively distorted when the four sides of the block were finally built, and the block courtyards were partially, or even totally, filled in. However, the dimensions of the blocks proposed by the engineer generated a new type of dwelling. This was a house of over 200 square metres that opened up to the facade, but also to the enormous interior of the block through a closed gallery or an open terrace.

Cerdá’s blocks. Via Wikipedia Commons.

The city combined good urban planning and good architecture and the Eixample, though not as green as it should have been, has nevertheless become emblematic of Barcelona. Of course, it is not a perfect project. We have already talked about the excessive crowding of the blocks. But the biggest problem is perhaps car mobility. Noise and pollution threaten quality of life. This is why it is necessary to adopt strategies that create an efficient, desirable and sustainable mobility. On the other hand, mass tourism complicates the lives of local people and raises housing prices. This makes access to good housing difficult and dwellings to be subdivided.

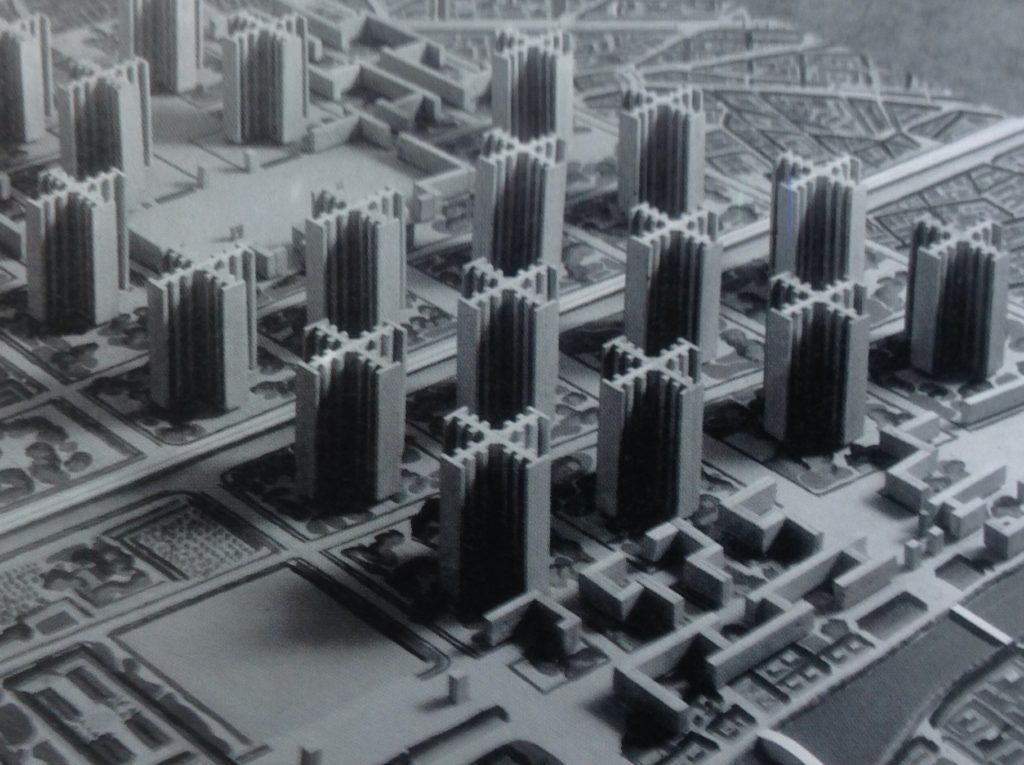

In contrast to the urban planning of Cerdá, or of his counterpart Haussmann, the one who first demolished and then built the monumental Paris, the 20th century saw urban proposals of a very different kind. From Le Corbusier’s Voisin Plan to American suburban housing, the proposed architecture was characterized by inhabited areas (whether collective or private housing), with a private plot of land around them, which could be reached by car. As Beatriz Colomina pointed out in her recently published book X-Ray Architecture, Le Corbusier made constant references to the issue of health in his texts. For example, in La ville radiuse published in 1935, he inserted medical texts alongside his projects. The Swiss architect advocated for the demolition of the existing city in order to build new blocks of flats on whose roofs people could exercise. And although, as Colomina points out, structures such as the 1930s tuberculosis sanatoriums served to implement the incipient modernity, sometimes the results were not the best. This would be the case of cities like New York, where the public official Robert Moses built hundreds of collective houses for the poorest sectors of society, the so-called “projects”.

Voisin Plan, Le Corbusier. Via Wikipediacommons.

Situations like the present one revive the ideas that the 19th and 20th century hygienists, and Le Corbusier and Cerdá, for different reasons, wanted to include in the dwelling: light, air, green spaces and (once we are out of quarantine), adequate mobility. However, in contrast to Le Corbusier’s tabula rasa, the US writer and theorist Jane Jacobs must be considered. Mixed uses, collective spaces and public day-to-day life are fundamental axes of community life, which we are keen to recover. Also, these also serve to build united, responsible communities that are more respectful with the environment.

It is perhaps the concept of ruralizing the city that could summarize many of our needs. Domestic spaces must be sufficiently dimensioned. It is important to recover compartmentalization, fixed or mobile, to favour the multifunctionality of housing and the possibility of diverse and different situations occurring in it throughout the day or the year. The modern paradigm of the minimum dwelling, which puts technical equipment (household machines) before space, must be forgotten. Households must be dignified and must respect and enable the lifestyles of the people who live in them. In addition, ideally, homes should have outdoor accessible space, terraces, patios, balconies. And if this is not possible (and as we will not be forever confined), definitely, sufficient sunlight. Replacing balconies with windows was one of the recent great mistakes.

Furthermore, buildings, blocks, and streets must not forget about collective spaces: block courtyards, squares, wide sidewalks, the ones that Cerdá and Jacobs defended tenaciously. Mobility must be part of urban planning, seeking alternatives to private cars, encouraging walking, cycling and public transport. The advantages of this are clear in cities of intermediate scale. Their more accessible urban planning may give us some clues. Since a bright, spacious and pleasant home is fundamental in life.

The cover image has been made by Therence Faircloth.

Leave a Reply