The relationship between the architectural interior and the exterior has always been a key aspect when thinking about domesticity. Geographic reasons, which mainly have to do with climate, and cultural ones, linked to society and tradition, define the architectural limit between inside and outside.

In the West, the opening of large windows was accepted and celebrated as soon as technique allowed fabricating them. The transparency ideals spread across the planet in the second half of the 20th century, along with other Modern notions. But the panoramic window would soon clash with non-Western traditions. Other cultures valued different ways of getting the light in the domestic interior. Sunlight was worked and articulated through architecture with elements such as latticework.

In the warmest countries, from India to the Iberian Peninsula, light has been a good whose quantity and incidence had to be controlled. In the Far East, there was too another understanding of light in the interior space, again different from the one that Modernity was exporting. Light was a material to be sifted and reflected inside architecture.

Traditional architectural techniques, from different parts of the world, have been reinterpreted by contemporary architects, interested in more sustainable ways of adapting to the climate, of designing home interiors, and in creating the space for certain kinds of social relations.

The latticework that covers part of the facade of Nirvana Home by AGi architects, provides a subtle transition between interior and exterior. Inside, it is combined with other architectural elements to generate intimacy gradations in domestic spaces.

Mashrabiya

In Islamic architecture, the mashrabiya is a type of window characterized by the presence of a wooden decorated latticework. It usually takes the form of a balcony looking over the street. Intimacy – a culturally fundamental element, solar protection – unavoidable in a hot climate, and decoration are key elements in the definition of these small architectures. Like much of the vernacular architecture, the design of the mashrabiya is very intelligent. In first place, it enlarges the room, without restricting traditional ways of life. Secondly, the arrangement of the openings allows good ventilation. Enlarged openings in the lower and superior parts makes the coldest air enter from below and the hot air go out through the top. In addition, the mashrabiya protects passers-by in the street from the sun and rain.

Maison es Suhaymi. El Cairo, Egipto. Image by Gérard Ducher, via Wikipedia Commons

Jaali

In India, jaali or jali is the name given to a type of screen or perforated wall. It is used to divide rooms, but also as doors or windows. Jaalis have usually calligraphic, geometric, and vegetal motifs. The total plane of the screen dissolves into multiple holes. Neither the direct rays of sun, nor its reverberation, can cross the jaali, whose thickness is similar to the size of its orifices. This way, it provides privacy in the hot and humid climate of India.

Jaali, Red Fort, Delhi. Imagen by V.Sathyamurthy, via Wikipedia Commons

Between latticework and Brise Soleil

Josep Lluis Sert, one of the most significant Modern architects, included the latticework as part of the construction elements of his International Style. The exiled Catalan architect, then living in Harvard, used it, for example, in the American Embassy in Baghdad. Modernity, apparently, was devoid of references, being almost pure abstraction and functional response: a scientific architecture. But, in reality, it had multiple vernacular influences. In this case, Sert used a typical resource from his homeland that related perfectly to the climate of the Asian city. This way, the Spanish architect drew a line connecting Spain and Iraq, and also that connected vernacular architecture and Modernity. The façade proposed by Sert for the embassy was solved through this complex latticework composed of geometric shapes, repetitions, symmetries and other techniques so characteristic of oriental architecture.

Mechanized tradition

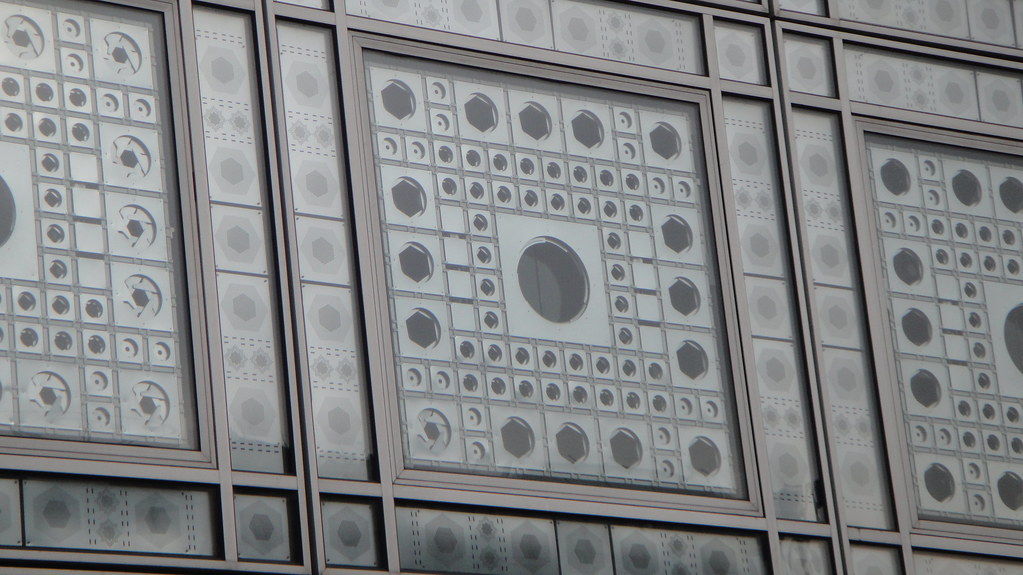

Postmodernity was also interested in latticework. The architecture that followed the Modern Movement understood the need of adaptation to context. Along with this acknowledgement, new technical developments converted the vernacular elements into prolific design resources. They allowed to combine an aesthetic experience with the solution of functional problems. An example of this is a classic of the late twentieth century architecture, the Institut du Monde Arabe designed by Jean Nouvel in Paris. The large block of steel and glass, pure in its overall form, was decorated with elements similar to those of the mashrabiya. 240 square panels that grouped 30,000 small mechanical steel diaphragms were connected to photosensitive sensors, which opened and closed according to the light intensity.

Instituto del Mundo árabe. Imagen de Joselu Blanco via Flickr

Architecture as a garment

Gottfried Semper insisted on the etymological relationship between certain words relating to architecture and textiles. For example, in German, Gewand, garment, contains the word Wand, that is, wall. In 1851, Semper published “The Four Elements of Architecture“. In this text, the German architect tried to figure out a general theory of architecture through four elements. One of them was enclosure, which originally would be made of woven walls.

«Wickerwork, the original space divider, retained the full importance of its earlier meaning, actually or ideally, when later the light mat walls were transformed into clay tile, brick, or stone walls. Wickerwork was the essence of the wall».

Four Elements of Architecture, Gottfried Semper, 1851.

The curtains of Lilly Reich

The red curtain of the Barcelona Pavilion is unforgettable. A large, red velvet curtain, at the large window that overlooks the square facing the pavilion designed by Mies van der Rohe with Lilly Reich. Two years before the construction of this pavilion, the two designers presented the Café Samt & Seide, a pavilion for the German silk industry, at the Die Mode der Dame exhibition held in 1927. The photos of the installation show a group of small spaces that flow one into the other. They are defined through orange, black and red velvet curtains, and also through yellow and black silk fabrics. All were suspended from curved lanes. Materials build the essence of space, something characteristic of Reich’s work.

Shōji

In Japan, partitions were always mobile, so that the house could be dismantled and ventilated in summer. The rice paper panels create an interior environment that establishes a fundamental relation with the ideal domestic space in traditional Japan: «And so it has come to be that the beauty of a Japanese room comes from a variation of shadows, heavy shadows against light shadows». Light in the Japanese house is another, one that creates an atmosphere of a dream, of unreality, in which the dark colors and the golden tones are emphasized.

«The light from the garden steals in but dimly through paper–paneled doors,and it is precisely this indirect light that makes for us the charm of a room».

Katsura Imperial Villa. Image by Tomoaki Ueda via Wikipedia Commons

The well-known text by Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, wrote as early as 1933, deals precisely with the difficult relationship between Japanese arts and Modernity. The concepts of hygiene, lighting or domestic functions that each of the two styles promote are almost incompatible. Tanizaki wonders, how to live by the Japanese tradition, while accepting the comforts brough from the West?

Perhaps now, after the crisis of Modernity, and the continued questioning of Postmodern ideas, integrating the values of both genealogies is a crucial point.

Leave a Reply